[ad_1]

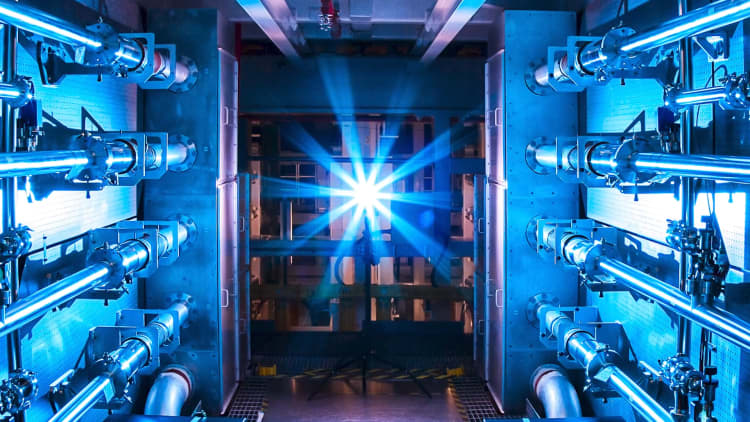

Physicist Stephen Wukitch stands next to the partially disassembled now defunct fusion reactor core at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Plasma Science & Fusion Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on January 25, 2023. – The lab is working with partners to build a new fusion reactor testing core.

Joseph Prezioso | Afp | Getty Images

The top regulatory agency for nuclear materials safety in the U.S. voted unanimously to regulate the burgeoning fusion industry in a different way than the nuclear fission industry is, and the fusion industry is celebrating that as a major win.

As a result, some provisions specific to fission reactors, like requiring funding to cover claims from nuclear meltdowns, won’t apply to fusion plants. (Fusion reactors cannot melt down.)

The nation’s top regulatory body for nuclear power plants and other nuclear materials, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, announced the results of its vote on Friday.

“Up until now, there was real uncertainty about how fusion would be regulated in the United States — this decision makes clear who will regulate fusion energy facilities and what developers will have to do to meet those regulations,” Andrew Holland, CEO of the industry group, the Fusion Industry Association, told CNBC. “It is extremely important.”

Other differences include looser requirements around foreign ownership of nuclear fusion plants, and no need for mandatory hearings at the federal level during the licensing process, Holland explained.

The decision had been in the works for some time. On Jan. 4, the staff of the NRC had submitted three recommendations to the Commission’s decisionmaking committee for how to regulate fusion. Those three options were to regulate nuclear fusion in the same way nuclear fission is regulated, regulate them based on the materials involved in the process or take a hybrid approach of the two options, Scott Burnell, spokesperson for the NRC told CNBC.

In that earlier communication, the staff of the NRC suggested regulating fusion like fission “is a poor fit with our rules,” Burnell told CNBC. But the decision wasn’t final until the NRC Commission voted.

The 93 nuclear reactors currently operating in the United States are all nuclear fission reactors, meaning that they generate energy when a neutron slams into a larger atom and splitting in two, thereby releasing energy. The electricity generated by nuclear fission is considered clean energy by the U.S. Department of Energy because it generates no greenhouse gas emissions. And nuclear power reactors deliver massive quantities of power: Half of the carbon-free energy generated in the U.S. comes from nuclear power reactors.

However, nuclear fission reactors also create waste that remains radioactive for thousands of years.

(L-R) US Under Secretary of Energy for Nuclear Security, Jill Hruby; US Energy Secretary, Jennifer Granholm; Director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Kimberly Budil; White House Office of Science and Technology Policy Director, Arati Prabhakar; and National Nuclear Security Administration Deputy Administrator for Defense Programs, Marvin Adams hold a press conference to announce a major milestone in nuclear fusion research, at the US Department of Energy in Washington, DC on December 13, 2022. Researchers have achieved a breakthrough regarding nuclear fusion, a technology seen as a possible revolutionary alternative power source.

Olivier Douliery | Afp | Getty Images

Nuclear fusion happens when two smaller atoms slam together to form a larger atom, releasing energy, and is the way the sun makes power. Nuclear fusion does not produce the same kind of long-lasting radioactive waste that nuclear fission does, but it’s very hard reaction to recreate on Earth. Because nuclear fusion creates virtually limitless quantities of energy with no greenhouse gas emissions and no long-lasting radioactive waste, it has become an area of intense interest to scientists and innovators working to commercialize the process as a climate change solution.

Private fusion companies have already raised about $5 billion to commercialize and scale fusion technology and so the decision from the NRC on how the industry would be regulated was a big deal for companies building in the space.

“It’s definitely a very good thing. We’re very pleased that the NRC Commissioners recognized that fusion energy is entirely different from nuclear fission and therefore should not be regulated in the same way,” Pravesh Patel, the scientific director for fusion startup Focused Energy, told CNBC. “I think this decision and the clarity it brings is very positive for the fusion industry and removes a major area of uncertainty for the industry.”

Commonwealth Fusion Systems, a startup spun out of MIT that’s raised more than $2 billion from a notable collection of investors, also supports the decision from the NRC, calling it “a regulatory approach that will enable the U.S. to be a global leader in commercial fusion energy” in a written statement shared with CNBC.

Helion, another fusion startup, says the decision leaves the runway clear for it to deliver its stated goals. “This approach provides a clear and effective regulatory path for Helion to deploy clean, safe, and effective fusion energy,” Sachin Desai, general counsel for Helion, told CNBC. “It is now incumbent on us to demonstrate our safety case as we bring fusion to the grid, and we look forward to working with the public and regulatory community closely on our first deployments.”

The approach to regulating fusion is akin to the regulatory regime that is currently used to regulate particle accelerators, which are machines that are capable of making elementary nuclear particles, like electrons or protons, move really really fast, the Fusion Industry Association says. Particle accelerators are fundamental to high-energy physics research, and they have been used to innovate in any wide variety of industries, including medicine, according to the Department of Energy.

Technically speaking, fusion will be regulated under Part 30 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Jeff Merrifield, a former NRC commissioner, told CNBC. The regulatory structure for nuclear fission is under Part 50 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

“The regulatory structure needed to regulate particle accelerators under Part 30, is far simpler, less costly and more efficient than the more complicated rules imposed on fission reactors under Part 50,” Merrifield told CNBC.

“By making this decision to use the Part 30, the Commission recognized the decreased risk of fusion technologies when compared with traditional nuclear reactors and has imposed a framework that more appropriately aligns the risks and the regulations,” Merrifield said.

[ad_2]