[ad_1]

Bleached grooved brain coral, center and left, and bleached boulder brain coral on the right. Photo taken on August 1.

NOAA, coral reefs, Florida Keys, coral reefs, coral bleaching, climate change, warm oceans

Coral reefs off the coast of Florida are being hit by a mass bleaching event due to record high ocean temperatures, and early indications suggest a global mass bleaching event could be underway.

“This is a very serious event,” Derek Manzello, the coordinator of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Coral Reef Watch Program, said on a conference call with reporters Thursday. And it’s especially severe in the oceans off the coast of Florida.

Permanent damage to Florida’s reefs could have notable economic impacts on the state’s economy.

Coral reefs provide between $678.8 million and $1.3 billion worth of economic benefit to Florida, including $577.5 million in recreational diving and snorkeling, and $31.2 million in commercial fishing, according to estimates compiled by NOAA. Reefs support fisheries and tourism and the associated hotels and restaurants in those coastal economies, said Ian Enochs, a research ecologist a NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, on a call with reporters on Thursday.

They’re also a first line of defense for coastal communities against storm activity, Enochs said.

“Reefs are also really important for buffering storm energy and hurricane wave action that would otherwise pummel our shorelines and our coastal infrastructure,” Enochs said. “They are living walls that breaks that energy from hitting hitting our shores.”

About a quarter of marine life associate with coral reefs at some point in their lives, and if reefs get eroded and lose some of their “structural complexity,” they lose their capacity to be a home to as many marine species, Manzello said.

Most of Southeast Florida and the Florida Keys are currently under a level two alert, which means that bleaching and significant mortality is likely, according to NOAA’s definitions. The Sentinel climate research and monitoring site in the Florida Keys has recorded 100% coral bleaching since late July.

But coral reef scientists have identified reefs with some level of heat stress symptoms in waters stretching from Columbia to Cuba.

“Florida is just the tip of the iceberg,” Manzello said.

This is a photo of the coral reef called Cheeca Rocks, located within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, taken on June 30, 2023, before coral bleaching occured.

Photo courtesy NOAA

This is a photo of the coral reef called Cheeca Rocks, located within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, taken on July 24, 2023, after coral bleaching occurred.

Photo courtesy NOAA

Record hot oceans in an El Niño year

Coral reefs grow best in water temperatures between 73 and 84 degrees Fahrenheit. Sea surface temperatures broke the previous record of 89.6 degrees Fahrenheit in the Florida Keys on July 9 and have exceeded that level for 28 of the last 37 days, Manzello said.

When corals suffer heat stress, they expel zooxanthellae, an algae symbiote that they need to survive. This is called coral bleaching.

Coral bleaching has happened before in Florida. There have been eight mass coral bleaching events that have impacted the entire Florida Keys since 1987, Manzello said. But this year, the heat stress started a full five to six weeks earlier than ever before, Manzello said, and it’s expected to last through late September to late October.

Corals can recover from bleaching events if conditions moderate sufficiently quickly, although they may have reduced reproduction capability and greater susceptibility to disease for some years after. But already, some parts of the coral in the Florida Keys are experiencing the accumulated heat stress that is twice what scientists expect is the amount they can take, Manzello said.

Ian Enochs observing the Cheeca Rocks corals in Florida on July 31.

Photo courtesy NOAA

“We hear the word unprecedented thrown around all the time, but allow me to qualify that word with the facts: Florida’s corals have never been exposed to this magnitude of heat stress. This heat occurred earlier than ever before,” Manzello said. “A big concern is that temperatures are reaching their seasonal peak right now, so this stress is likely to persist for at least the next month. These corals will experience heat stress that is not only higher than ever before, earlier than ever before, but for longer than ever before. This is key because the impacts to corals is a function of how high the heat stress is and how long it lasts.”

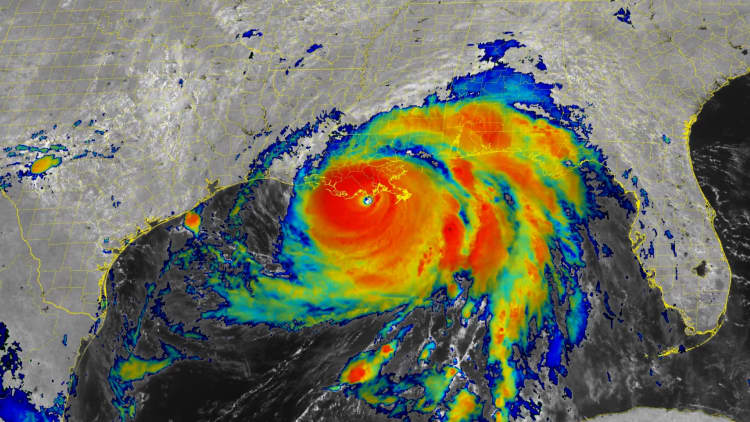

These predictions could moderate if a hurricane or tropical storm comes through Florida waters because these storm events cool the ocean waters and the coral environments.

While Florida coral are suffering some of the worst bleaching, scientists have confirmed coral bleaching off the coast of Columbia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico, and Panama in the Eastern Tropical Pacific and off Belize, Cuba, Mexico, Panama, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands in the Atlantic.

“We’re talking about thousands upon thousands of miles of coral reefs undergoing severe bleaching heat stress,” Manzello said.

There have been three global coral bleaching events: In 1998, 2010, and a three-year period from 2014 to 2017, which occurred on the heels of a strong El Niño weather event.

“So what is concerning now is that, again, we are right on the cusp of a very strong El Niño,” Manzello said. El Nino is a weather pattern that has the potential to bring warmer temperatures and more extreme weather events. “Now, it’s still way too early to predict whether or not there will be a global bleaching event, but if we compare what is happening right now to what happened in the beginning of the past global bleaching event, things are worse now than they were in 2014 to 2017.”

A ‘Herculean rescue effort’

In recent weeks, scientists have been executing a significant and coordinated effort to rescue corals from the oceans off the coast of Florida.

Photo courtesy NOAA

A massive and coordinated effort is underway in Florida to protect some of the corals facing existential threats. Some species have been taken to land-based tanks, and others are being relocated to deeper, cooler waters. Approximately 150 elkhorn coral and 300 staghorn coral fragments have been rescued, said Andy Bruckner, a research coordinator at NOAA’s Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, on Thursday’s call with reporters.

“This represents every remaining unique genotype or genetic strain of these species that’s known to exist in the reefs in Florida,” Bruckner said. “This has been a Herculean effort for what’s been done to date.”

The unprecedented coral bleaching conditions are hard for scientists and preservationists, but they’re leaning in, said Jennifer Koss, director of the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program, on the call with reporters on Thursday.

“People are anxious, they’re depressed, but at the same time, they’re pitching in and doing everything that they can because we all know, this is not a resource we can afford to lose. We cannot — full stop — afford to lose coral reefs,” Koss said. “The ecosystem and societal values that they provide to coastal communities, particularly Florida along the southeast and in the Keys, is critical to sustaining economies and the safety of the people that live there. So as horrible as it is, we’re in it, and we’re going to fight to the death to figure out how to make sure corals can buy enough time to withstand this event.”

[ad_2]